Introduction

The participation of children and young people in sport has always been high on the international policy agenda (Nicholson, 2010). Sport is seen as an effective and relatively cheap way of bringing about many positive outcomes for individuals and societies (Bailey, 2018b), and there is a widely held belief that playing sport is an inherently worthwhile activity in its own right (Martínková, 2013). Yet, there have been many concerns expressed about relatively low levels of participation, both within sport in general, and in specific sports including golf (Audickas, 2017; Lera-López & Marco, 2018).

Clearly, there must be reasons why this situation has arisen in golf, but research to help address it has been extremely limited. This is especially the case with regard to research into children and young peoples’ experiences of their engagement in golf, and the role that coaches might play in influencing those experiences. For example, Bailey & Cope’s (2017) review of factors that impact on young people’s behaviours and attitudes to golf coaching noted that, “very little work has been done that would have enabled this specific purpose to be met. In fact … no peer reviewed papers were found on the topic of this project” (p. 3). The urgency and importance of studies on the topic of young people’s engagement with golf seem unarguable.

This article offers the first expert consensus study aiming to identify practical approaches to increasing the participation of children and young people in golf. A group of professional and qualified golf coaches were led through an iterative process of gathering, refining, and prioritising their thoughts on two key questions:

-

What should be done to attract more children and young people into golf?

-

What barriers currently exist to more children and young people coming into golf?

It is our aim that the insights generated by this process will contribute to the on-going discussion about engaging and retaining children and young people in sport, and, in particular, in golf.

Background

There is mounting evidence that children and young people can derive a range of benefits from participation in sport (Bailey, 2006; Bailey et al., 2009), although specific benefits achieved from different forms and patterns of activity are established (Farahmand et al., 2009; Oosterhoff et al., 2017). The physical health benefits of participation in sport have been acknowledged for some time (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000), and there is a growing body of research investigating the psychological and mental health benefits (Biddle & Asare, 2011). Children who participate in sport have been found to score higher on scales for happiness, mental health and physical health compared to non-participants in sport (Snyder et al., 2010). Regular participation in sport has also been linked to better quality of life (Khan et al., 2012), and more positive school experiences (Bailey, 2018b). Research with golf, the focus of this article, has reported “improved physical health and mental wellbeing, and a potential contribution to increased life expectancy” (Murray, Daines, Archibald, et al, 2017, p. 1).

Sports clubs seem to be distinctively valuable settings for providing a stable and sustainable setting for sustained engagement (Nielsen et al., 2016), but patterns of children’s and young people’s participation vary considerably around the world (Hulteen et al., 2017), with increasing concerns expressed about decreasing levels of activity in many developed countries (Physical Activity Council, 2019; Riddoch et al., 2004). Generally speaking, boys participate in sport more frequently than girls and are more physically active from childhood into adolescence (Bailey, 2018b), although this pattern is mediated by a range of factors, such as socioeconomic status and environmental characteristics (Vella et al., 2014). These patterns are partially explained in terms changing societal influences, such as the emergence of social media and electronic recreation and reduced independent mobility (Bailey, 2018a). Studies have also identified factors that affect participation at the individual level, including those that promote participation (e.g., close fit between the child’s interests and the sporting activities on offer, positive coaching climate, and readily accessible practice sessions), and those that obstruct it (e.g., inappropriate coach-child ratios, limited space, or mismatched expectations between coaches and those of children and their parents) (Curran et al., 2015; Wall & Côté, 2007; Welk, 1999).

One of the most significant and compelling sets of findings from research into young people’s experiences of sport is that benefits merely represent potentialities, and that positive developmental trajectories are dependent not just on the inherent structural and normative characteristics of activities, but also on the psychological, social, and cultural ‘climate’ in which they are presented (Agans et al., 2013; Duda, 2013; Whitelaw et al., 2010). These factors help account for some of the inherent complexity of young people’s engagement with sport (Toms & Colclough, 2012). They also explain the central importance of the coach as a ‘orchestrator’ (Jones & Wallace, 2006) of the different elements of the session, the wants and needs of the participants, and the numerous other factors that contribute to learning and development (Toms, 2017; Wright & Toms, 2017).

Golf has experienced waning levels of participation and an aging base over recent decades (IBISWorld, 2018). For example, the UK’s ‘Taking Part’ survey (DCMS (Department of Culture, Media), 2015) found that only 4.6% of 5-10-year olds and 5.8% of 11-15-year olds surveyed participated in golf. So, while the sport has proved to be popular among retired people, it has struggled to recruit and maintain younger players. In addition, golf is often perceived as a sport attracting players mainly from a higher socio-economic status, and mainly boys and men (England Golf, 2018). So, golf is traditionally perceived as being an ‘elitist’, adult, and relatively expensive sport to play (England Golf, 2014), and it is not currently a popular activity for school-aged children (DCMS (Department of Culture, Media), 2015). The average cost for a yearly golf membership for an adult in England is £850; for junior members, it is £120 (Bailey & Cope, 2017). Juniors aged under 12 are unlikely to play on their own or only with friends so it is also probably unlikely that a non-playing parent accompanies their child member around a course. In that case, a child and parent membership costs about £1,000 per annum. Member-based clubs remain the most common setting for golf in the UK (Syngenta, 2014). Alternatives are available, such as pay-and-play, but these can also be costly, and often lack the professional coaching support typically provided by clubs. The issue of cost is perennial one in studies of children’s participation in sport, and parents frequently report lack of disposable income as a cause of their children’s low levels of physical activity (Thompson et al., 2010), and challenges become magnified with multiple siblings within a family household (Harwood & Knight, 2009). Prompted by such concerns, a number of organisations have introduced programmes targeting juniors, and under-represented sub-groups, such as girls (England Golf, 2019; Golf Foundation, 2018; PGA, 2019). There has little systematic evaluation of most of these schemes, and it is sometimes difficult to judge the extent to which programme design, content, and pedagogy draw on peer-reviewed, empirical research, rather than the personal experiences and folk pedagogy of originators. Indeed, some sort of meta-analysis of the impact of these programmes could be a valuable addition to the empirical base of junior coaching.

Although under-researched, evidence supports benefits of participation in golf, especially with regards to physical health (Luscombe et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2017, 2018) and mental health (Winter, 2017). Farahmand, Broman, De Faire, et al (2009) produced a study of the health benefits of golf. Analysing a cohort of 300,000 Swedish golf players, the researchers found a 40% decreased mortality rate compared to non-players. While it is not possible to attribute causality in a study of this sort, the significant difference is suggestive. In contrast, research with juniors tends to focus on the transfer of life skills from golf to other aspects of life (Toms, 2017; Weiss et al., 2013, 2016).

A number of commentators and reports have raised concerns about issues of the accessibility and suitability of the culture of conventional golf clubs for young people (Golf Foundation, 2018; Haig-Muir, 2004; Kitching, 2011). Research into engagement in movement activities suggests that the cultural constraints of the sports setting can act as facilitators or barriers to access (Agans et al., 2013). Golf is unusual among sports in the extent to which in the coach can have limited influence over the wider culture and values promoted by the club committee. This does not apply to all coaches, of course, and some golf coaches now work relatively autonomously of host facilities. But the traditional coach-within-an-established-club model still seems to be the norm (England Golf, 2018). The consequence of this situation is that there can be aspects of young golfers’ experiences which would not have been designed or influenced by the coach had s/he the choice, but nevertheless determine the context in which the coach must operate. It has been suggested that this context has tended to reinforce traditional aims and practices, which are exclusionary to young people, especially girls (Kitching et al., 2015). Zevenbergen, Edwards & Skinner (2002) found that those exposed to golf clubs from an early age are more likely to assimilate to its culture, and this is more likely to be the case with boys. A survey by England Golf (2014) found that, on average, there were only 5 girl junior members per club. A related statistic was that at the time of this survey, on average, only 1% of new members in golf clubs were junior girls, compared with 7% of junior boys. Haig-Muir (1998) suggested that more males play golf because they are socialised into the sport from an early age, whereas girls are socialised away from golf. Senyard (1998) noted that where golf club rules and regulations limited the participation of women, gender was used as a way of constructing the social meaning of golf to wider society. The consequences of this situation can be serious:

“Out-dated practices, systems and structures, and the inflexible attitudes that riddle … Golf clubs have created a missing generation of female golfers with juniors, students, young married women, and women in the paid workforce all significantly underrepresented. Club Golf as it is does not suit these groups … nor does it attract them to the game. Solutions require a major cultural shift: a complete sea change in climates of thought, traditional practices, and, above all, golfing culture” (Haig-Muir 2004, p.78).

One conclusion that could be draw from these data is that golf is not succeeding in appealing to young people, and especially girls, or is not being perceived by them in a manner that fits with their motivation to participate.

The process by which junior players become members of most golf clubs can be a barrier to participation. For example, according to England Golf (2014), 5% of potential new members needed to provide proof of handicap, which immediately rules out beginners, novices, and those who have previously played golf independently of formal settings. 37% of applicants were required to undergo an interview, 33% were needed to be proposed by existing members, which were presumably parents in most cases, and 67% had to write a written application, which tends to disadvantage young people from lower socio-economic groups (Rivera & Tilcsik, 2016). Of course, there is variation between countries and clubs. In Switzerland, for example, adult golfers must complete a 3-part test to be able to play on golf courses alone, while children and young people have a simpler route, due to Junior Tees, although they are still “required to take tests” (Association Suisse de Golf, 2012, p. 4).

Zevenbergen and colleagues (2002) sought to understand the ways in which certain practices convey the meanings about what are valued aspects of golf club culture. Following a group of young cadet golfers (8-14 years), the researchers highlighted “certain aspects of the culture valorised within the golf club context” (p. 1). For example, those young people who had been involved with golf from an early age participated more effectively in the club, largely because they were more likely to value similar aspects of the club’s general atmosphere. Those who came to golf later were exposed to a golf culture that promoted and valued often contradictory values and practices. For this group of players, there were few options other than to assimilate into the golfing culture in an attempt to learn the distinctive values of golf. This was essential if the young player was to remain a member, but it required considerable effort and was not readily achieved. Similar findings were reported in a recent study of ten golf clubs in Ireland and Northern Ireland (Kitching et al., 2015). Following an extensive period of observations, interviews and participant research, the authors highlight “formal golf traditions and selective club practices [that] contribute to a golf club culture that inhibits involvement, valorises status and legitimises inequality” (p. 190). They concluded that change is needed to loosen the shackles of tradition and promote progress and growth of the sport. An earlier, non-peer reviewed, evaluation of an Irish initiative to introduce girls to golf and to encourage girls to take up golf club membership is also worth mentioning. Kitching (2010) used different terms to describe similar phenomena as described above. The ‘Girls N Golf’ programme was led by golf club volunteers and a PGA coach, and content included basic tuition on a variety of golf skills such as putting, chipping and driving. Most sessions took place at the golf club, but groups could also avail of other local facilities such as a driving range, and pitch and putt, or par three courses. Despite the positive experiences reported by many of the participants, the evaluation identified the resistance of clubs to adapt their policies and practices to make it easier for young girls to join and play regularly. Moreover, and as has been discussed earlier in this report, the potential for young players to join member-owned or proprietorial clubs is severely limited by restrictions on new junior memberships. Kitching’s (2011) PhD thesis on the same theme concluded, “although limited, this evidence conveys how golf clubs are not inclusionary environments for young people” (p. 71).

In addition to young people’s family circumstances, there are more intractable barriers to playing golf in many countries. For example, young people and their parents often cite bad weather as a reason that prevents them from participating. Young people consider this to have a demotivating effect, while it has been found that parents are generally unwilling to afford their children the opportunity to play outside in such conditions (Cope et al., 2013). Another environmental barrier identified by young people is the intrusion or simply the visibility of older youth in their play spaces (Eyre et al., 2014), and parent’s anxieties about letting their children play unsupervised in local community contexts (Jago et al., 2011). While some of these environmental constraints may not relate directly to golf, there is some evidence that young people can feel uneasy about playing golf among adults (Syngenta, 2014). In this respect, the golf club environment can be seen to be relatively hostile by young people.

Generally speaking, there has been a gradual move away from adult-orientated approaches to sports provision, and towards those designed to act as a foundation for positive, healthy engagement and development for children and young people, and cognisant of their distinctive biological, psychological and social characteristics (Bailey, 2012; Bailey et al., 2010; Toms, 2017). Significant differences between children and adult’s engagement with sport that impact of their experience of coaching have been identified, some of which are summarised in Table 3 (below).

Methods

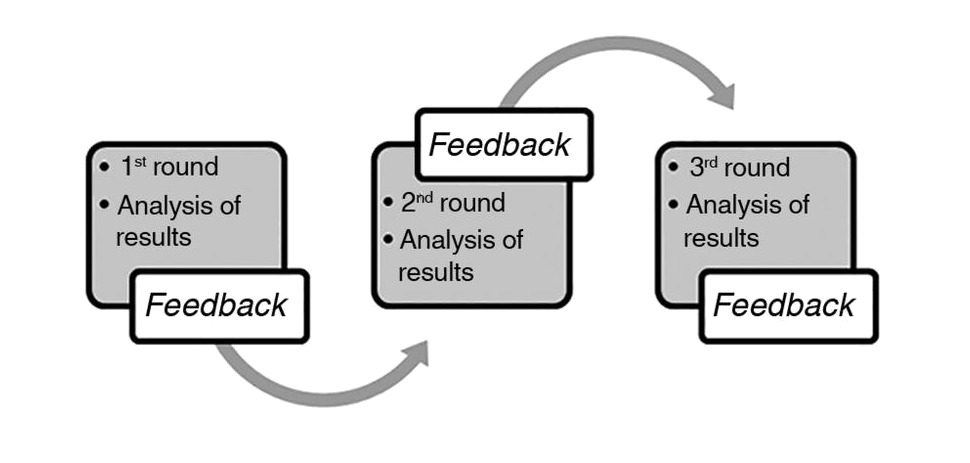

The methodological approach chosen for eliciting the ‘expert’ community’s view was a 3 stage Delphi study, “a unique method of eliciting and refining group judgement based on the rationale that a group of experts is better than one expert when exact knowledge is not available” (Kaynak and Macauley, 1984, p. 90). This approach has been widely used in research where the aim is to gain expert consensus (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). The primary rationale of employing this method is that it provides experts an opportunity to share their ideas, individually and as part of a group in a manner, which avoids potential confrontation of their views (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Anonymous throughout the process, and multiple rounds of controlled feedback help the research team to limit the influence of comments from peers (Hsu & Sandford, 2007). This method is a well-established way of improving group decision-making by seeking opinions without face-to-face interaction, and has been usefully described as “a method of systematic solicitation and collection of judgements on a particular topic through a set of carefully designed sequential questionnaires, interspersed with summarised information and feedback of opinions derived from earlier responses” (Delbecq et al., 1975, p. 10). The Delphi procedure seeks to establish the extent of consensus within a community, and has a number of distinctive virtues with regard to this aim: group decision-making; involving acknowledged experts in the field; producing findings with generally greater validity than those made by any individual; with anonymity and no geographical limits; and time for reflection of responses (Goodman, 2016; Powell, 2003). The Delphi method was chosen for this particular study as it offered a mechanism for exploring ideas and the formation of an informed group judgement, especially as empirical evidence was limited.

Of course every research tool has limitations. For the Delphi Method, the central conceptual challenge is to justify the criteria for the identification of the experts within the study (McKenna, 1994). The approach taken in the current study was utilised the expertise of a group of professional coaches associated with the Swiss Professional Golfers Association, participating in a specialist ‘Junior Coaching Summit’. In doing so, the intention was to capitalise on the tacit association between professional status and relative expertise (Taylor & Garratt, 2013).

The Delphi process was used to collate expert opinions on the two main research questions:

-

What should be done to attract more children and young people into golf?

-

What barriers currently exist to more children and young people coming into golf?

The basic approach in this study involved the gathering of the opinions of a discrete group of subject experts, and then submitting those opinions to a structured rounds of analysis and reorganisation. So, the experts are invited to engage with increasingly aggregated iterations of the group’s decision-making.

The basic Delphi process used in this study is summarised in Figure 1:

In other words:

-

A panel of experts was recruited, made up of people who were judged able to offer credible opinions on the two problems (see below);

-

The researchers articulated these two problems;

-

The experts gave their initial responses to the two problems as statements of action (‘Round 1’);

-

The researchers analysed, weighted, and ranked the experts’ responses, and invited the experts to rank the collated responses (‘Round 2’);

-

The researchers analysed and weighted the revised and ranked list of responses, and invited the experts to rate (using a 7-point Likert scale) the new list (‘Round 3’);

-

The ten statements that were ranked and rated most positively by the group were selected as the final list.

Overall, this study can be understood as a scoping study. The evident lack of previous quality research into young people’s engagement with golf, and the apparent lack of agreement about how best to progress, suggest that a qualitative investigation might usefully act as a preliminary launchpad for subsequent research.

Recruitment and Sample

Panel sizes in Delphi studies vary considerably, but guidance suggests recruiting between 15 and 35 experts, with an expectation that between 35% to 75% of those invited actually participate (Gordon, 2007). As stated earlier, a convenience sample of experts was recruited participants at the first Junior Coaching Summit of the Swiss Professional Golfers Association (with preparatory messages circulated in advance). The Swiss PGA presents an interesting setting for this study for a number of reasons, such as its relatively small exposure of the golf within the country (compared to, for example, the United States and the United Kingdom and Ireland), and multi-national professional membership (Swiss PGA, 2019). The main virtue of the group, though, was that offered a suitable timing and setting for a non-probabilistic, purposive sample which was judged necessary for a scoping study like this (Battaglia, 2008). The initial criterion for inclusion was qualified golf professional status, although it was decided to add a junior organiser with a strong involvement with the topic. This resulted in a sample of 29 experts with a range of golf coaching experience (mean 17.25 years, SD=10.42 years). Email contact details were gathered for all participants, and used to communicate information about the subsequent iterations of the Delphi process.

Procedure and Analysis

The Delphi process was explained to the group of experts, and all questions were answered. The aims and research questions for the project were explained, and participants were informed that their engagement with this project was entirely voluntary, that all responses would be anonymised, and that they could withdraw at any point without explanation. Response rates for the different stages of the study were as follows:

- Stage 1: 29

- Stage 2: 21

- Stage 3: 19

This represents a 66% completion rate. The first round involved completing a hand-written list of up to five priorities they believed were especially relevant to the two questions: (Q1) attracting more children and young people into golf; (Q2) and barriers currently existing to more children and young people coming into golf. They were also asked for a contact email address for subsequent communications. The second and third rounds of the Delphi were administered electronically, using an online software program (www.surveymonkey.com) via a link embedded in an email message.

The first round of data-gathering produced 130 discrete responses to Q1, and 122 responses to Q2. These answers were analysed and coded in order to identify meaningful categories. Individual responses were collated into a single list, and checked for overlap and duplicate content. After eliminating redundancies, a simple process of content analysis of the remaining statements, in which coding categories were derived directly from the text data, identified categories that would organise the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). 36 categories were found for Q1, and 29 categories for Q2. In the second stage, the golf coaching experts were presented with the categories and invited to rank them “in terms of importance”. The average ranking for each answer choice was calculated; the answer choice with the largest average ranking was judged to be the most preferred choice overall. The ten categories with the largest weighting then formed the basis of the third round of the Delphi process. The experts were invited to indicate their agreement / disagreement with each category in a 10-point Likert scale.

Findings

The weighted averages of findings from the third, final stage of the iterative expert consensus process is presented in Table 2 and 3.

Results and Discussion

The purpose of this research was to answer two questions: What should be done to attract more children and young people into golf? And, what barriers currently exist to more children and young people coming into golf? From our analysis of the data, we identified five themes in response to our first research question, and three themes in response to our second research question. In this section we will present data generated from the Delphi study, which related to each of these themes supported by theorizing from the golf coaching and broader sports coaching literature.

What should be done to attract more children and young people into golf?

Initially focusing on those within close proximity of the club

A critical factor in attracting more young people to play is their access to an environment suitable for play (Allender et al., 2006). Evidence from golf-specific research supports this claim, with the finding that participation is significantly greater for those living close to golf clubs (Toms & Colclough, 2012). It is known that 50% of adult members live within a 5-mile radius distance to a golf club, and 50% of junior members are children of adult members. So, a strategy of targeting children and young people living within a short distance from clubs, such as the use of mail drops, open days and other outreach, and schools programmes in which classes are invited to the golf clubs, could be potentially fruitful strategies, if only one that is part of a wider approach (Association Suisse de Golf, 2012).

Engaging the family and friends

Parents are critical social influencers for sports and many other activities. They are the first and most enduring presenters of sports to children, and have been found to influence their children’s experiences of sport in a number of ways (Côté, 1999). For example, parents have the greatest influence on children’s perceptions of sport competence, particularly during childhood, and these perceptions can have dramatic effects on children’s willingness to enter the sporting space. Reflecting this, there is increasing evidence that clubs where coaches and parents collaborate and communicate closely offer more positive sporting experiences than those where parents are kept ‘at arm’s length’ (Knight et al., 2016; Stefansen et al., 2018). The junior offers developed by clubs and coaches should, therefore, be inclusive and framed around family involvement and community.

Inclusive and community driven approaches have other benefits, too. Parents can also provide practical support, including paying for lessons and equipment, providing transportation, providing emotional support, and also give their children a sense of their and the community’s perceptions of which activities are most suitable, valuable and acceptable (Dunn et al., 2016). Parents who encourage their children’s participation (Kirby et al., 2013), or who themselves have a background in sport, are more likely to become involved in their children’s sports participation (Bois et al., 2005), a finding that seems highly applicable in the context of golf. Evidence suggests that there is a fine-line between parental support and interference (Smoll et al., 2011), so the introduction of a parent education system, with guidance on ways to appropriate support for children in golf, could be a worthwhile investment. Indeed, research undertaken in the United Kingdom (Toms & Colclough, 2012) found that 97% of PGA professionals have a family member who plays the game.

Evidence also supports the claim that peers can significantly influence young people’s attitudes and behaviours with regard to sports participation (Salvy et al., 2008). Older children serve to initiate other children into sport via co-participation, modelling being active, and providing support and encouragement (Jago et al., 2009). Previous research has highlighted participation with friends to be a determining factor in why children take part in sport and physical activity, as well as a primary cause of what they value about sport and physical activity (Cope et al., 2013; Syngenta, 2014). Existing junior participants could, therefore, be encouraged to ‘bring a friend’ or sibling. However, in light of the potential social stigma discussed earlier in this article suggests that this strategy should be considered with caution.

Age-appropriate opportunities

Whilst not the dominant theme, the importance of exploring practices that are specifically orientated towards the distinctive needs and interests of junior players was, perhaps, the most common among the data. The golf coaches offered a range of strategies for promoting participation, including the use of junior tees, adapted courses, family-friendly competitions, shorter golf courses, faster games, and child-only areas. These sorts of ideas acknowledge empirical findings that stress the need to challenge traditional club cultures that retain commitments to a model of delivery based on adult-orientated values, practices, and timetables (Kitching, 2010, 2011; Kitching et al., 2015; Zevenbergen et al., 2002).

The role of the golf coach for adults is a topic perennial interest, not least because it has evolved to take a different form many other sports coaches. The distinctive setting in which most golf coaches operate (as part of a pre-existing club) has often led to them being engaged for short-term error-correction, rather than as the leader of an on-going group (Wright & Toms, 2017), and employed on an hourly, self-employed basis. This is quite different from the model of coaching often presented as best practice for children, and suggest that clubs and organisations need to consider alternative models of funding, perhaps based on long-term, project-based engagement of coaches.

Children’s coaches have been described as architects of sport learning environments, structuring it to foster healthy and holistic development (Mallett, 2013). Central to the design of a supportive learning environment is the way coaches interact with children and how they explicitly attempt to deliver on the agreed learning outcomes (e.g., the ‘four Cs’ of positive youth development - competence, confidence, connection, and character; Vierimaa, et al, 2012). They can also be significant role models for young people, and their behaviours can either encourage sustained participation or contribute to attrition (Côté & Gilbert, 2009). Effective coaches of the young deliver activities that are enjoyable, challenging, and promote perceptions of competence and belonging (Wall & Côté, 2007), and the lack of fun, in particular, has been reported as a frequently cited reason for attrition from sport (Butcher et al., 2002). This can be aided by framing sessions according to the wants and needs of junior golfers. Age is an important variable in this context (Bailey, 2012). In addition, some may prefer more relaxed sessions that are socially based, whereas others may be more focussed on skill acquisition and playing the game more competitively.

What barriers currently exist to more children and young people coming into golf?

Accessibility

The pivotal role of parents as primary socialising agents, particularly for younger children was introduced earlier in this paper. Alongside this, parents are also often the gatekeepers to their participation, as children are usually reliant on the support of their parents in numerous ways. This situation seems especially pertinent in the context of golf, as has already been discussed. ‘Pay and Play’ and public golf are alternative options, but they can also be relatively expensive if accessed regularly and with personal equipment. Therefore, the cost of playing golf can create a barrier to participation, a claim supported by the finding from earlier research that a lack of disposable income is frequently cited as a cause of their children’s low levels of activity engagement (Thompson, et al, 2010). This issue becomes magnified as the number of siblings within a family household increases, especially if those children have different interests. Studies of children identified as potentially talented, especially those recruited to a pathway, suggest that financial issues become even more problematic. In such cases, children from single-parent families and lower-socio-economic background can find themselves significantly disadvantaged compared to their peers, irrespective of ability or interest (Bailey et al., 2010).

The experts in the consensus group offered a number of strategies for combatting the problem of inaccessibility, as is revealed elsewhere in this article. Anecdotal evidence suggests other potential approaches:

-

golf equipment can be subsidised by the facilities to ensure this is not a barrier;

-

Selected members to take juniors onto the golf course, offering a safe and positive experience of the game;

-

One-off experiences, such as golf holiday camps;

-

Sponsorship programmes can be established to invite payments from adult members each year. These could fund camps, trips, subsidised coaching, and so on.

Underlying these and other strategies discussed in this paper is a broader conception of the roles of the coach. As is discussed elsewhere, golf coaches traditionally adopt a rather narrow and utilitarian position within a club. In order to work within the contexts outlined above, however, it may be necessary to reframe the coach’s role more broadly to include facilitating activities, spaces and opportunities within the club.

Golf clubs as welcoming social site

It has been argued that a successful, positive sporting experience can be useful characterised in terms of a good ‘fit’ between individual and activity: “A positive fit is achieved when an individual (behaviour, attitudes, skills) interconnects well with a physical activity context (type of activity, teaching style, motivational climate), resulting in positive outcomes for both individual and context” (Bailey, 2018b, p. 220). A vitally important aspect of the fit between young players and a sporting activity is the setting in which that activity takes place (Agans et al., 2013). The values, meanings, and expectations that constitute the culture of a specific club can communicate a message that is, to some degree, inviting or not. Individuals vary enormously, of course, yet it seems reasonable to suppose that the facts of children’s experiences and development translate into certain generalisable principles of a distinctive ‘child culture’ (Bjørkvold, 1989). The universality of play behaviour during childhood is now well-established, as is its adaptive value (Gray, 2013). Bjørkvold (1989) explicitly linked play to children’s cultural expectation such that it represents their “experimental laboratory for learning, where the conquest of reality - seen and unseen - is continually being anticipated” (p. 33). A related theme is fun and enjoyment, which often has a hedonic character, especially during early childhood (Dismore & Bailey, 2011). Play is, of course, notoriously difficult to define and categorise. However, there does seem to be a consensus in the literature that playful behaviour prioritises means over ends, and collaborative engagement rather than outcomes (Gray, 2013).

Both academic commentators and the expert group raised concerns about the lack of opportunities in some golf clubs for suitable places for children and young people to spend time with friends, to play sport and socialize afterwards, as well as spaces for family members of different generations to socialize (Kitching, 2010, 2011; Kitching et al., 2015). Zevenbergen and colleagues (2002) identified a ‘hidden curriculum’ within the golf clubs they visited, in which young players who failed to fit in with the existing culture of the club were quietly marginalised and excluded. This was achieved via rules and regulations covering behaviour and participation in the golf habitus. The consequences were that they were excluded from the power and status enjoyed by those who assimilated into the culture of the club. Kitching and colleagues (2015) and the Golf Foundation (Syngenta, 2014) reached similar conclusions. The latter is, perhaps, particularly relevant, since it involved discussions with junior players, themselves. Utilising four in-depth focus groups with 14-15 year olds, and 16-17 year olds (two interviews with each group respectively, with one group of non-golfers and another being with golfers), the researchers found that some young people spoke about golf as being advertised as an ‘old mans’ sport, and that it is only through playing with younger people that they realised this was not the case (Syngenta, 2014). For the older group, in particular, the time it took to complete a round of golf was a factor that negatively impacted on their participation. People in this age group often had the pressures of studying for examinations or working and, therefore, wanted to spend some of their free time socialising with friends. More flexible ways of playing golf, such as 6-hole or 9-hole formats, were considered attractive solutions to this problem. However, the same clubs’ policies seemed to forbid such practices, such as juniors having to play 9 holes with members, be assessed by coaches, or be supervised until the age of 18. Both groups of young people reported that the culture of golf clubs meant that they felt they had to control their behaviour in ways that made them feel uncomfortable. Furthermore, it was perceived that the lack of opportunities for social interaction meant limited opportunities to spend time with other young people (Syngenta, 2014).

It is important to acknowledge, however, that while some young people feel opportunities for social interaction through golf are limited, this is not to say that clubs do not have the facilities and therefore potential to facilitate it. According to the 2014 membership survey (England Golf, 2014), 95% of clubs have a bar, whilst 78% have a restaurant, and 26% have a coffee shop. Alongside a children’s play area, these facilities have been associated with an increase in membership applications. Consequently, there appear to be appropriate spaces to encourage young people to socialise with other young people. Whilst the evidence is currently limited, it does seem that the potential uses of these spaces are not currently being realised.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has several limitations. The Delphi has some inherent limitations, such as: the length of the process; influence on the responses due to particular question formulation; and difficulty in assessing and fully utilising the expertise of the group because they never meet (Murry & Hammons, 1995). The implementation of this Delphi study took account of these perceived disadvantages. There were also some limitations internal to this study. First, while a specific context and population were identified in advance, the potential for biases remained due to self-selection, under-coverage, non-response, and sampling errors. Second, while the Delphi method allowed for participation from a group of experts, it could not result in the same sort of interactions as a live discussion. This might have been exacerbated by delays in responses (although response times were relatively fast). Third, it was also possible that the information received back from the experts provided limited innate value. These limitations are inherent in the method employed, rather than the study per se. Nevertheless, it is important that they are acknowledged, as our intention is to scope and initiate further enquiry in what is undoubtedly an under-researched area.

The sample of golf coaching experts was drawn from a national organisation. European Golf coaches tend to come from a diverse range of countries, so these coaches might be more heterogeneous than would be found in other sports. However, there might be value in undertaking parallel consensus studies, especially in non-European contexts. The most important step, we believe, is to undertake empirical, longitudinal research into the efficacy of the methods and strategies generated by this Delphi project.

Conclusion

This is the first expert consensus study seeking to identify practical approaches to increasing the participation of children and young people in golf. It was our hope that the insights generated by this process might contribute to the on-going discussion about engaging and retaining children and young people in sport, and, in particular, in golf.

A range of ideas were generated about how best to attract more children and young people into golf? Many of these ideas reiterate findings from general research into children’s participation in sport, such as the involvement of family and friends as significant social influencers, the initiation of age- and developmentally appropriate practices, and addressing the need for economic affordability. Others are less familiar, such as targeting proximate groups of children and young people. Proposals related to changes to the golf club culture might be understood as context-specific examples of the fundamental and universal need to discover ways of finding a better ‘fit’ between the wants and needs of children and young people, and the distinctive characteristics of sporting opportunities. So, although this study explicitly addresses golf, some of the lessons drawn could usefully be generalised to sport and other forms of physical activity, in general.