Trust in Automation in Golf

As in many sports, equipment in golf has evolved with the aim to improve the golfer’s performance. One piece of equipment that has seen a steep increase in usage is the distance measuring device (DMD). DMDs are primarily used to measure distance and yardage estimation on the golf course to aid in club and shot selection. When a golfer has accurate information regarding yardage to the green, for example, he or she can then choose the appropriate club and shot to optimize the possibility of shot execution. As a result, although dependent on shot execution, accurate yardage estimation should improve a golfer’s performance and score.

There are a variety of types of DMDs. These include GPS technology and laser technology, and can come in forms of handheld devices, watches, and laser range finders. Each type of device has its own advantages and disadvantages. For instance, while laser range finders are accurate in measuring the distance in a straight line between the laser and a target, it is not very helpful when a golfer needs to execute a shot towards a blind target. On the other hand, devices using GPS technology can be beneficial as they often provide distance to multiple points at the same time (e.g., front, middle, and back of putting green) without the need to see the target; however, they also rely on course maps and satellite signals that can be impacted by elevation changes and weather conditions.

Since 2006, tournament committees have had the option of including a Local Rule (under the former R&A’s Rules of Golf, Section 14-3) to allow golfers to use DMDs that measure distance only. With new rule changes in 2019, DMDs will be allowed in amateur tournament play unless a Local Rule states otherwise (R&A Rules of Golf, 2019, p. Section 4.3). In 2014, both golf’s governing bodies [i.e., Royal & Ancient (R&A) and United States Golf Association (USGA)] decided they would allow DMDs to be used during amateur championships and their qualifiers. In 2017, the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) announced it would be testing the use of DMDs on lower-level tours, including the Web.com tour, the primary feeder to the PGA tour. Lastly, both the R&A and USGA also announced in 2017 that DMDs could be used in competition as early as 2019.

DMDs are a form of automation. Automation is a “device or system that accomplishes (partially or fully) a function that was previously, or conceivably could be, carried out (partially or fully) by a human operator” (Parasuraman et al., 2000, p. 287; Parasuraman & Riley, 1997, p. 231). Automated systems can differ in the type and level of support they provide to the user ranging from simply acquiring and analyzing information to making and enacting decisions (Parasuraman et al., 2000). DMDs can be classified as information acquisition automation in that they provide information regarding the distance to the green and can also provide information regarding hazards on the course; but the user still needs to make decisions regarding club selection and execute the shot.

Regardless of level or type automaton, one factor that contributes to whether a person uses or relies on automation is their trust in the automated system. Reliance is a term commonly used in the context of automation to state that the user is either actively engaged with or is referring to the automation during their task. Trust in the context of automation has been defined as “The attitude that an agent will help achieve an individual’s goals in a situation characterized by uncertainty and vulnerability” (Lee & See, 2004, p. 54). Of particular note, this definition of trust emphasizes the goal-directed nature of the relationship, which is relevant when considering technology that aims to increase performance in a specific context. Interpersonal definitions of trust tend to be less focused on goal or task performance, and more on a general willingness to be vulnerable to another party (Mayer et al., 1995). Returning to the context of automation, the end behaviour of interest is reliance, or use of the system. Clearly, there are other factors beyond trust that can influence the intention to use and the use of the automated system including the user’s confidence in their ability to perform the task themselves.

In the context of DMDs, golfers form beliefs about the DMDs by gaining information from many sources ranging from advertising or informal interactions with other golfers around the clubhouse. Their affective evaluation of this information may be influenced by their general propensity to trust technology and, if/when they use the system, their experience with the system. This level of trust will factor into whether the golfer intends to use or purchase the DMD; however, other factors including the cost of the system and the golfer’s self-confidence in estimating yardages on his or her own may also influence their intention to use the system.

Returning to reliance on automation in general, it is of interest to whether the user is relying on automation appropriately. To elaborate, misuse of the automation occurs when human relies on the automation when it is inappropriate to do so, hindering performance; whereas disuse occurs when the human does not rely on the automation when it would be beneficial to do so (Parasuraman & Riley, 1997). Appropriate reliance is relying on or using the automation in contexts that will benefit overall human-system performance. Appropriate reliance is facilitated through trust calibration where the level of trust matches the automation’s abilities (Lee & See, 2004). Therefore, trust plays an important role in the decision of whether to use an automated system. Trust may be especially important in the recreational context of golf because at the amateur and club level it is completely a consumer based choice of whether to purchase and use the automated system in contrast in the professional golf setting where use is prohibited. Consequently, high performing amateur golfers with a goal of playing professionally may have to adjust from playing with a DMD to playing without.

As noted previously, self-confidence also plays an important role not only in yardage estimation, but also overall sport performance. In fact, the positive correlation between confidence and sport performance is one of the most consistent findings in the sport psychology literature (Feltz, 2007). Feltz (2007) further argues that although self-confidence is believed to impact sport performance, the nature of its relationship has not always been clear. That is, while the correlation is a robust one, whether there is a causal relationship, and what the direction of that relationship is has yet to be conclusive.

In the golf literature, (Bois et al., 2009) found a positive relationship between confidence and performance in a small group of professional golfers. While their correlation was moderate to weak, they argue that their sample size (N=41) may have limited their results. Moreover, they argue that perhaps self-confidence did not discriminate successful and unsuccessful players (i.e., making the cut vs. not making the cut in a professional tournament) because it is correlated with other variables of performance such as anxiety. One could also argue that self-confidence in professional golfers may have much less variability (i.e., ceiling effect) considering the actual skill required to become a professional golfer. Furthermore, confident individuals tend to be more effective in using cognitive resources that are required for athletic success (Hays et al., 2009). For example, a golfer confident in his/her abilities to estimate yardage may also be better to take notice of course elevation, wind direction, and course condition; all factors that could also help determine club and shot selection. A skilled golfer will have a fairly good knowledge of how far he/she can hit each one of their clubs; therefore, being confident in their own yardage estimates may lead to greater overall confidence in shot selection and subsequent shot execution. On the other hand, having little confidence in one’s ability to estimate yardage may lead to hesitation in club selection, which in turn may lead to poor shot execution.

To date, there is limited information regarding the factors that affect a golfer’s trust in DMD automation and confidence in their own yardage. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine how a golfer’s confidence in his or her own abilities to determine yardage and trust in technology impacts how they use and rely upon DMDs. To this end, golfers were invited to complete an online survey regarding their use of DMDs as well as their self-confidence in estimating yardage and their trust in DMDs. It was hypothesized that golfers that used DMDs would have a higher level of trust in DMDs than non-users. We also predicted that DMD users would lower self-confidence in estimating yardage than non-users. Further, in addition to DMD use, factors such as age, gender, years of golf experience and handicap were entered into regression models that predicted trust and self-confidence to explore whether these factors had a positive or negative association with trust in technology and confidence in yardage estimation.

Methods

Participants

Eight hundred and nine participants began the questionnaire and a total of 661 participants completed the questionnaire (23% female). Any participants with missing data from either the trust in automation or confidence in self measures were removed from further analysis. For the 661 participants who completed the questionnaire (i.e., with no missing data), the mean age was 56 years (SD = 14 years; range = 18 – 87 years), with a mean of 28 years of playing experience (SD = 14.8; range = 1 – 67). The mean handicap factor of participants was 13 (SD = 7.62; range = +2.4 – 38).

Design and Procedure

The study was a one-time cross-sectional design using an online survey. Participant recruitment included emails sent through the provincial golf association, private club newsletters, and social media (Twitter and Facebook). A link to the online questionnaire was included in the recruitment messages, participants followed the link, and once the questionnaire was completed, were invited to enter a draw for a $100 gift card.

Measures

Participants completed an online survey comprised of questions including years playing, age, handicap, sex, their confidence in their own abilities, and trust in automation.

Trust in DMD automation

The portion on trust used a modified, validated scale on trust in automation (Jian et al., 2000). The scale retained all of the original items but the wording was changed slightly to better relate to the context of golf. The questionnaire included 12 questions where participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale their level of agreement with each stem (1 = Completely disagree; 7 = Agree). Sample questions included: “I am suspicious of the DMD/GPS’s outputs”, “I can trust the DMD/GPS”, and “The DMD/GPS’s information will increase my performance.”

Self-confidence in determining yardage

To measure confidence, we modified the trust questionnaire to make the wording relevant to assess golfer’s confidence in their own manual estimation abilities (i.e., determining yardage without the use of technology). Maintaining consistent questions (where possible) between measures of confidence in self and trust in the automated system is a typical approach for studies that investigate the relationship between confidence in self and trust in automation (Rajaonah et al., 2008). The questionnaire included 10 questions where participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale their level of agreement with each stem (1 = Completely disagree; 7 = Agree). Sample questions included: “I am confident in my estimates of yardage”, and “I am not always able to come up with good information regarding yardage to benefit my game decisions.”

Data analysis

For both the trust in technology and self-confidence questionnaire, all reverse scored questions were flipped so a higher number indicated more confidence or more trust. To get a global trust and global confidence score, each participant’s responses were averaged across the questions on each questionnaire. Two separate regression models for confidence and trust were built. Age, Gender (dummy code: Male – 0; Female – 1), Handicap, Years Playing and GPS Ownership (dummy code: no GPS – 0; GPS owner – 1) were forced entered into each model. The average confidence and trust scores each had a left skew, which led to the standardized residuals for each model having a leftward skew; therefore, the scores for each measure were squared. The results reported below are for the models using the squared confidence and trust scores.

To directly compare confidence and trust scores between DMD users and non-users, a 2 Group (user vs. non-user) x 2 Measures (trust vs. confidence) mixed ANOVA was run on the questionnaire scores.

Results

Bivariate correlations were run between the continuous predictor variables (Table 1). Unsurprisingly, there was a moderate correlation between Age and Experience and Age and Handicap. While this potentially could indicate there could be concerns with multicollinearity, collinearity diagnostics were all within acceptable ranges for both models (tolerance for all variables well above .2, smallest tolerance=0.58).

Confidence

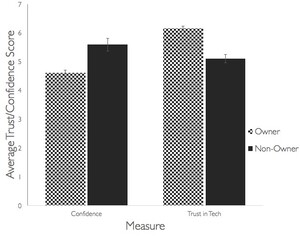

The scale reliability for confidence was high (Cronbach’s α = .92). The overall model was a significant predictor of confidence, F(5,656)=29.0, p<0.001, R2=.18. Individual coefficients in the model are presented in Table 2. Handicap, Years Playing and whether the golfer owned a DMD significantly predicted Confidence scores. There was a significant negative relationship between increasing handicap and confidence in estimating yardage; b=-.38, 95% CI [-.53, -.24], t(656)=5.1, p<0.001, where poorer performing golfers had lower confidence in estimating yardage. There was significant positive relationship between Years Playing and Confidence; b=.10, 95% CI [.0.02, .17], t(656)=2.6, p<0.01, where golfers who had been playing longer reported more confidence in estimating yardage. Finally whether participants owned a DMD or not significantly predicted confidence; b=-10.4, 95% CI [-.12.5, -8.23], t(656)=9.5, p<0.001, where participants who owned DMDs had lower confidence in yardage estimation than those who did not own DMDs (Figure 1). No other predictors were significant.

Trust in Technology

The scale reliability for trust was high (Cronbach’s α = .89). The overall model was a significant predictor of trust in technology, F(5,656)=35.7, p<0.001, R2=.21. Individual coefficients in the model are presented in Table 3. Gender, Handicap and whether a golfer owned a DMD significantly predicted Trust in Technology scores. There was a significant relationship between Gender and Trust in Technology; b=2.32, 95% CI [.50, 4.13], t(656)=2.5, p<0.05, where females had higher trust in technology than males. There was a significant negative relationship between Handicap and Trust in Technology; b=-.25, 95% CI [-.37, -.13], t(656)=4.0, p<0.001, where poorer performing golfers had less trust in technology. Finally, there was a significant relationship between DMD ownership and Trust in Technology; b=10.5, 95% CI [8.69, 12.3], t(656)=11.4, p<0.001, where golfers who owned DMDs had higher trust in technology that golfers who did not (Figure 1).

Comparison between Trust and Confidence

The main effect of group (DMD users vs. non users) did not significantly affect questionnaire score, F(1,660)=0.01; p=.92, η2=1.6*10-4. There was a significant effect of measure, F(1,660)=44.5 p<0.001, η2=.06. This effect, however, was modified by a significant two-way interaction, F(1,660)=154; p<0.001, η2=.19. As shown in Figure 1, DMD users had higher scores for trust in DMDs than for confidence in estimating yardage, t(532)=21.3, p<0.001. Conversely, DMD non-users and significantly lower scores for trust in DMDs than for confidence in estimating yardage, t(128)=3.45, p=0.001.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine how a golfer’s confidence in his/her own abilities to determine yardage and trust in technology impacts how they use distance measuring devices (DMDs). Golfers who did not own DMDs had higher confidence in estimating yardage but lower trust in automation than those who owned DMDs. Further, better performing golfers and those who had been playing longer had higher confidence in their yardage estimates. Regarding trust in DMDs, women had higher trust in DMDs than men and poorer performing golfers had less trust in DMDs. Each of these results will be discussed in turn.

Confidence

Participants with a lower handicap (i.e., greater ability) had a greater level of self-confidence in estimating yardage. This is not greatly surprising as mastery and demonstration of ability are two of the most salient sources of self-confidence in sport (Vealey & et al, 1998). While this study did not examine or take into account participants’ actual ability to estimate yardage, yardage estimation, done with or without the use of technology, is an integral component to golf performance. Therefore, higher skilled golfers, in addition to shot execution, may also be better able to estimate yardage. Future research should examine the actual ability of higher and lower skilled golfers in estimating yardage without the aid of a DMD.

Furthermore, golfers who had more years of playing experience also had greater levels of self-confidence in estimating yardage. If estimating yardage without the aid of technology is considered an important skill in golf, then the more experience or practice a golfer has in estimating yardage, the better they may become at it, and in turn, leads to higher self-confidence. This process also lends itself to the mastery and demonstration ability sources of sport self-confidence (Vealey & et al, 1998). Also, since DMDs have really only been on the market for less than 20 years, those golfers who have greater years of playing experience would have had a longer time in needing to estimate yardage on their own. In contrast, younger golfers or those with less playing experience have had access to DMDs for most of their playing career.

Additionally, research by (Wilson et al., 2004) examined the sources of self-confidence in masters-level athletes. Most of the sport literature stems from sample populations of young adults, where most sport participants are found. However, the present study included a relatively older sample (mean age = 56 years, age range = 18-87 years), which could also indicate greater years of playing experience. Wilson and colleagues (2004) found that situational favourableness was a poor predictor of self-confidence in masters-level athletes in comparison to younger athletes. They argued that experienced competitors might view situational favourableness as something fickle and not quite relevant or important in this particular population of athletes. In relation to the golf context, situational favourableness would refer to the lie of the ball on the golf course, course conditions, and even distance to the green or hole. Consequently, an older and more experienced golfer may be less affected by other factors in an instance where he or she had to determine yardage on their own.

Finally, participants who owned DMDs had lower confidence in yardage estimation than those who did not own DMDs. As DMDs can be relatively expensive, if a golfer is self-confident in his or her ability to estimate yardage, they may be less likely to spend the additional money on purchasing a DMD. On the other hand, if a golfer is lower in self-confidence in estimating yardage, he or she may be more likely to purchase the DMD with the goal of improving golf performance.

An additional explanation may be the relative novelty of DMDs in golf. As previously mentioned, DMDs have only been allowed on golf courses since 2006. The participants in the current study have a mean of 28 years of playing experience therefore; most participants in this study would have played for years without the use of a DMD. If a golfer has a higher level of self-confidence in estimating yardage, perhaps they are less likely to purchase or use one once they become available. Future research could examine why golfers choose to purchase or use DMDs.

Trust

Participants who owned a DMD had a higher level of trust in the technology. This is unsurprising given that the use of a DMD is a consumer decision. Similarly to participants with greater levels of self-confidence, participants who do not trust DMD technology are unlikely to purchase the device. Further, without experience with the device, non-DMD users do not get the chance to receive feedback or information about the automation that may increase their trust in automation (Lee & See, 2004). In contrast, participants who purchased the technology may have a higher baseline level of trust in either DMD technology or technology as a whole which made them willing to spend capital to use the automation. Further, once they have acquired the DMD, the user is able to interact and receive feedback on the automation’s performance, a critical factor for developing trust in the system.

Golfers who had a higher handicap had less trust in the DMD. This may be because they did not trust the additional information provided by the automation would to improve their game. Considering the level and type of automation, the DMD is information automation, it does not perform decision-making (e.g., selecting the correct club to use) or actually execute the task for the user (Parasuraman et al., 2000). If the golfer cannot execute a shot or select a club to the precision of yardage information provided by the DMD, the DMD is unlikely to provide any additional performance benefit.

Females were found to have a greater trust in technology compared to males. This finding is in line with previous research in social psychology (Haselhuhn et al., 2015) that found that females not only tend to trust more than males, but also are more likely to restore trust following a breach of trust.

Considering Trust and Confidence Together

Considering the results from trust and confidence together provides some insight into DMD use. As mentioned above, those with low trust in the technology or high confidence in their own yardage estimates are unlikely the purchase the system. This group of golfers therefore does not receive feedback on how their performance relates to that of the automation and whether the automation is trustworthy for use. Those who purchase the automation on the other hand receive additional information including insight into how it works and performs. This information is critical for trust development (Lee & See, 2004). However, in relation to lower confidence among DMD users, what is not clear is whether golfers are purchasing a DMD because they do not have confidence in their yardage estimates or that use of the DMD actually decreases their confidence in their own yardage estimates. One common side effect of automation use is the loss of manual skill (Casner et al., 2014; Young et al., 2006). Further, users may see the precision afforded by the technology and realize they could not estimate yardage with such precision, decreasing their confidence. Such level of precision afforded by DMDs may only be relevant to the most highly skilled golfers. For example, the difference between 5 yards for a very highly skilled golfer may mean a change in club or choice of ball trajectory, if one has the skill to control either shot components. However, for a lesser skilled golfer (yet still relatively skilled), a difference in 5 yards may mean very little. Nevertheless, having that level of precision, may offer comfort to any golfer thus leading to a greater sense of confidence in club and shot selection.

Limitations

One limitation of the current study is due to its cross-sectional nature; we can only speculate as to the directional nature of this relationship. Future research should use a longitudinal design that explore how introducing a DMD devices affects trust in the device and confidence on manual yardage estimates. A second limitation is that our sample contains more DMD users than non-users. This may be due to the popularity of the devices. Anecdotal evidence from market reports in the U.K. suggests that 70% of golfers in 2015 own a DMD (Bossom, 2015). Another possibility may be that DMD users were more motivated to participate in a study on DMD use than non-users. Therefore, there may be DMD non-users (or even DMD users) who are more ambivalent to the technology than the non-users captured in our sample.

Another limitation is the variety of DMDs available on market (e.g., GPS, laser, handheld, watches, etc.). We did not discriminate between these in this study, focusing more on the general attitudes and feelings of trust in DMDs. Golfers may, however, have varying levels of trust on DMDs dependent on the type, brand, and model. Future research should examine these potential differences.

Practical Applications

In terms of applications to the DMD users, golfers and coaches should be aware that DMDs are to be used as tools. That is, the information provided by a DMD should be considered in decision and shot making but should not be the only information considered. A golfer must not only be confident in the yardage estimate, whether from a DMD or from one’s own estimate, but also show confidence using the information appropriately in club selection, confidence in shot selection, and confidence in shot execution. Further, being confident in one’s own estimates may come with time and practice, which may be hindered by the use of DMDs. Over-reliance on technology may inhibit a golfer’s ability to learn how to estimate yardage on their own, which may cause problems if the technology fails (e.g., loss of battery power) mid-round. Athletes and coaches may want to consider focusing on increasing one’s confidence in using both their own estimates and considering the information that the DMD provides.

From a golf industry’s perspective, we found that women tend to trust DMDs more than men. Perhaps DMD manufacturers could consider marketing DMDs specifically to women, since the majority of golf equipment marketing is targeted to men who golf.

While this study focused on the use of technology in the sport of golf, the increased use of technology and how we interact with it is relevant in many different sporting contexts. For example, runners using watches to measure their split times, rowers using technology to measure the stroke rates, and curlers using stop watches to estimate rock sliding times. Within these examples, we still see athletes who prefer to use some or none of the available technology. We also see rules in place by the sporting organizations regulating the use of technology. Future research should continue to examine the interactions between humans and technology, and how this interaction may directly or indirectly impact performance.

Conclusion

DMDs are increasingly popular in the sport of golf. The current study is the first to examine the relationships between DMD usage, and self-confidence in estimating yardage and trust in DMD technology. Results of the current study suggest that a golfer’s ability (measured by handicap factor), and years playing a positively related to self-confidence in estimating yardage, while DMD ownership is negatively related to self-confidence is estimating yardage. It is also suggested that females have a greater level of trust in technology in DMDs and that a golfer’s ability (measured by handicap factor) and DMD ownership positively predicted trust in DMD technology. Overall the study provides evidence that DMD use is related to trust in technology and self-confidence in yardage estimates. Further research should explore the directional nature of these relationships and the effects on golf performance. The knowledge gained from this study helps describe golfers’ beliefs and further research needs to investigate impact of these beliefs.